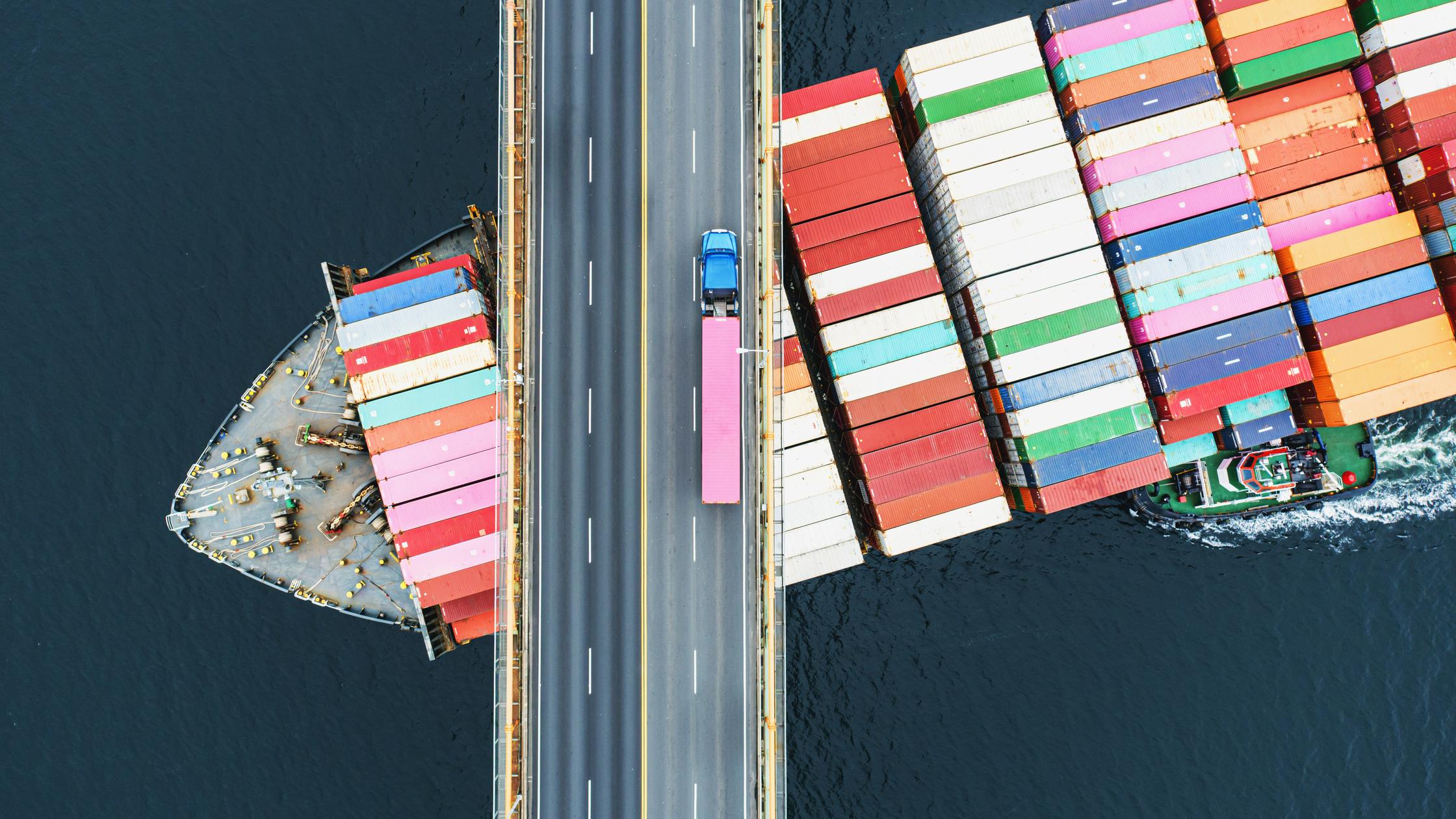

Stay up to date on the most relevant digital trust, EHS, and supply chain topics for your business. Our experts work on complex, multi-faceted projects across all industries to create best practices with a sustainable, compliant, and future ready position.

- Search BSI

- Verify a Certificate